How Bunkafu Notation Helps You

Structure and Elements of Bunkafu Notation

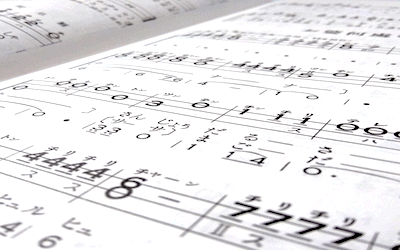

The top part of a typical piece of sheet music in bunkafu notation.

The Three Lines

The three lines in the notation represent the shamisen’s three strings. The lines are arranged the same way the strings are when you’re holding the instrument: The bottom line represents the thick string that lies closest to the player. The top line represents the skinny string that is farthest away from the player. The middle line… represents the middle string.

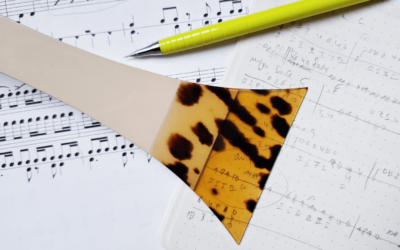

The three lines and the three strings as you see them when you hold the instrument.

Pitch

Pitch and positions on the big string (ichi no ito) when tuned over C.

The positions (numbers) are spaced a halftone apart. Thus, they correlate to all the white and black keys on a keyboard.

Corresponding piano keys for all positions on the thick string (ichi no ito) tuned over C.

Instructions: If you don’t have position markings on your shamisen’s neck yet but would like to have some, I recommend this article about Fujaku Strip and Positions and the corresponding Video in which I give detailed step-by-step instructions on how to find and mark positions.

Dashes

Note lengths compared: Western notation on the left, bunkafu notation on the right. Both follow the same logic.

Dots

Rests in comparison: In Western notation, you have to learn to differentiate between the different rest signs. In bunkafu notation the length of a rest is indicated the same way as a normal note.

Normal vs. dotted note. The dot lengthens the note by half of its usual time value.

Repetition Signs

Repetition of Measures

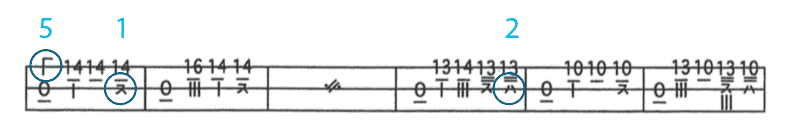

left image: abbreviation in a real-life example | right image: magnified abbreviation

Repetition of Sections

The repetition sign is at the beginning of the first measure and at the end of the last measure of the repeating section.

Technique Signs

Examples for oshibachi/suberi, sukui, and hajiki in the notation.

Examples for suri and uchi in the notation.

Example for keshi in the notation. The keshi is usually placed underneath a rest and indicates to not let the preceding note bleed into the rest/pause. This is achieved by muting the string and thus cutting the sound off.

False Friends: The tie uses the same sign as the suri, but should not be confused with it. The tie indicates that two consecutive but separately written out notes on an identical position are to be played as one single seamless unit. It’s always two same positions, for example 3 and 3. In shamisen notation you will find the tie spanning across a measure line. That indicates the note is to be continued past the measure line (thus the tie). You will only find ties in modern notations for shamisen. The suri on the other hand indicates an audible slide between two different notes. If you have two different positions, for example 3 and 4, it definitely is a suri and not a tie. .

Fingering

The Sheet Music’s Head Section

The Meter

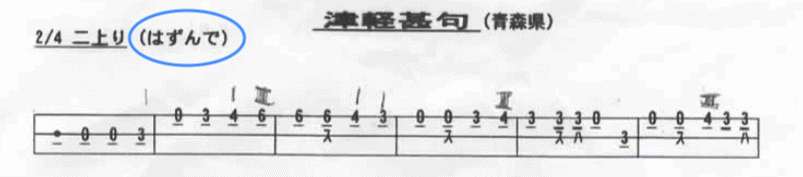

The sign for hazunde rhythm is placed next to meter and tuning. Sometimes you’re supposed to know that a piece is in hazunde rhythm so they don’t write it out. It’s probably assumed that the player has a teacher who would point out the piece being in hazunde to their student.

A direct comparison of what the notation looks like (top) versus what you’re supposed to actually play it like (bottom).

Help Make More Possible!

If you want to support the creation of more projects and tutorials, you can leave a tip in the coffee tip jar or support Shamisen-Zentrale on Patreon.

Other Signs

Practice, Practice, Practice

Watch the video here: