What Exactly Is a Scale?

The term scale appears in many contexts. It can refer to the division markings on a measuring instrument or a graded series of degrees within a phenomenon (like a scale of brightness levels). In everyday speech, we also use it metaphorically: “How would you rate the customer service on a scale from 0 to 5?” How many steps the scale has and how far apart they are depends on the context. There’s always a starting point from which one moves step by step.

In music, the starting point is a specific note or pitch — for example, “C.” On the shamisen, with the tuning C–G–C, that would be the open thick or open thin string. A musical scale spans one octave, for instance from the thick C string to the thin C string, or from the open thin C string up to position 10 on that string (again, C). Everything between those two points is divided into steps, which don’t have to be equal in size or number.

Scales on the Shamisen

If you have a fujaku strip attached to your shamisen’s neck, you can use it to see the standard points that make up a scale. From the open string to position 10, there are eleven marked points. When you play each position in order, they’re evenly spaced — these are called half steps (semitones). You can picture it on a piano: between one C and the next, play all the white and black keys in sequence. That’s the chromatic scale, which includes all the tones within an octave used in conventional music.

Good to know: On instruments like the shamisen, where you can glide smoothly from one pitch to another, there are countless tones between the marked positions — these are called microtones. In Western and Western-influenced music, the chromatic scale forms the foundation for most scales. In other musical traditions, and in some modern Western compositions, microtones are also used to expand the tonal palette.

Scales in Japanese Music

Within an octave — based on those eleven positions — players usually select just a few to create the specific set of tones for a piece. Another word for a scale in this sense is tone ladder (Tonleiter in German). This term might sound more familiar, though it often leads people to immediately think of the Western major and minor scales with seven notes. But both the number and spacing of steps can vary widely.

Just as major and minor scales became dominant in Western music (see also church modes), certain scales also became established in Japanese music. Japanese scales are typically based on five tones and are therefore called pentatonic (from the Greek penta, meaning “five”).

A scale defines the tonal “ingredients” of a piece. Depending on how you combine them, you can create endless variations.

Why Practice Scales?

When students are forced to play scales by their teacher, they often do it without energy or focus — and get little benefit from it. I’m a big fan of scales because I use them to direct my attention to specific technical aspects. Scales help me simplify complexity, create predictability, and give my mind some breathing room.

For me, they’re especially useful for:

-

- refining intonation (pitch accuracy)

- improving coordination between left and right hand

Scales and Intonation

When you slowly play a scale up and down, either in parts or as a whole, you can really focus on how each note sounds. Besides listening to pitch accuracy, this simple structure gives space to observe the tone quality of each fingered note: Does it sound soft or hard? Clear or dull? What changes if I press differently?

Clearing the Head

When you’re in the middle of a piece, your mind is juggling many elements at once — rhythm, phrasing, tone, emotion. The ear often doesn’t have the capacity to focus on precise pitch. Whether you personally care about “clean” intonation or not is up to you. But it’s an undeniable fact that your shamisen will sound richer and fuller when you hit pitches precisely. The tone opens up and shines. Your own music becomes more beautiful to listen to.

If you miss a note here and there in performance, that’s completely fine and doesn’t diminish a heartfelt delivery. But improving your awareness of when a note truly rings clearly — and training your hands to find those tones reliably — is something scale practice can develop beautifully.

The most important thing is always to have fun and enjoy what you’re doing. If scales help you get to know your instrument better, embrace them. If they just feel like a chore, find other approaches that feel better — and skip them entirely.

Practicing Scales on the Shamisen

So how can you practice scales on the Shamisen in a practical way? Using two examples – one for beginners and one for advanced players – I’ll show how scale exercises can playfully improve intonation, technique, and finger coordination.

Beginner Example

In my experience, the right hand is the trickier one. At the start of each practice session, I recommend first striking the open strings with the bachi to remind your hand how loose and effortless a relaxed strike feels. Once that feels good, add the other hand as a distraction: press a position, release, press again. Does the bachi hand stay relaxed? Then move on.

Gradually increase the left-hand activity — add another finger, or shift the same finger to a different position. As soon as more than one position is involved, scales become a great tool. You don’t have to invent new positions, and you’ll also be practicing something directly useful for songs.

Predictability, simplicity, repetition — these three qualities make scales such a powerful exercise.

Advanced Player Example

If your bachi hand struggles with a new striking pattern in a piece, it’s much more enjoyable to isolate that pattern and test it across different tones in a scale instead of repeating it endlessly in one spot. This keeps your ears engaged and develops finer control, since each position feels slightly different due to string tension.

I would first play the pattern on open strings, then add one fingered note, and finally switch positions. If the pattern falls apart, go back a step and start again with open strings.

Even if the pattern uses multiple positions, begin simple — open strings first, then add one position, and only expand from there.

If you want structured exercises for shamisen technique using scales, you can find regular new drills on my Patreon:: patreon.com/shamisenzentrale

Using Scale Knowledge to Improve Pieces

Knowing which scale a piece is based on — in other words, which tones it uses — is very helpful. It lets you consciously ignore irrelevant positions and reduces the overwhelming possibilities along the long shamisen neck. The mind relaxes. The fingers know they only need to access a small set of positions.

Modern compositions sometimes throw in “surprise” tones outside the scale (like secret ingredients), but traditional songs and folk repertoire rarely do.

More Room for Beautiful Tone

To learn a piece efficiently, it’s not essential but very helpful to study and listen to each position deliberately. Your ear learns not just pitch accuracy but also the character of the intervals between tones. Your hand learns the feel of moving between those positions. Your fingers develop a better sense of how firmly to press the string for a clear tone.

When you learn a new piece written in the same scale as one you already know, it becomes much easier because your hands are already familiar with those positions — they “remember” both where to go and how each one sounds. You don’t even need to practice scales separately for that effect — it happens naturally through repetition.

Scales, Solos, and Improvisation

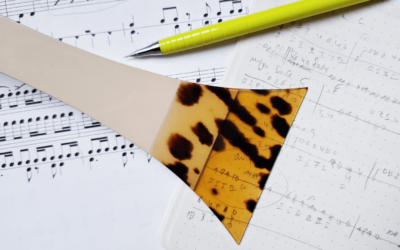

Eventually, when you start adding small solos or variations to pieces, you’ll encounter scales again — even unconsciously. Those tones are your “safe zone.” Some players discover them intuitively by ear, others prefer a clear structure to rely on. A playful, relaxed approach with attentive listening and trust in your musical instinct is ideal — but not everyone feels comfortable that way. Writing down the scale can give you a sense of clarity and calm when experimenting.

If you’re looking for an overview of the most common scales used in shamisen music, you’ll find it on my Patreon, along with regular new technique exercises based on different scales.

Watch the video here: